When jazz was born in the brothels of New Orleans in the early 20th century, its parents were musicians and mobsters.

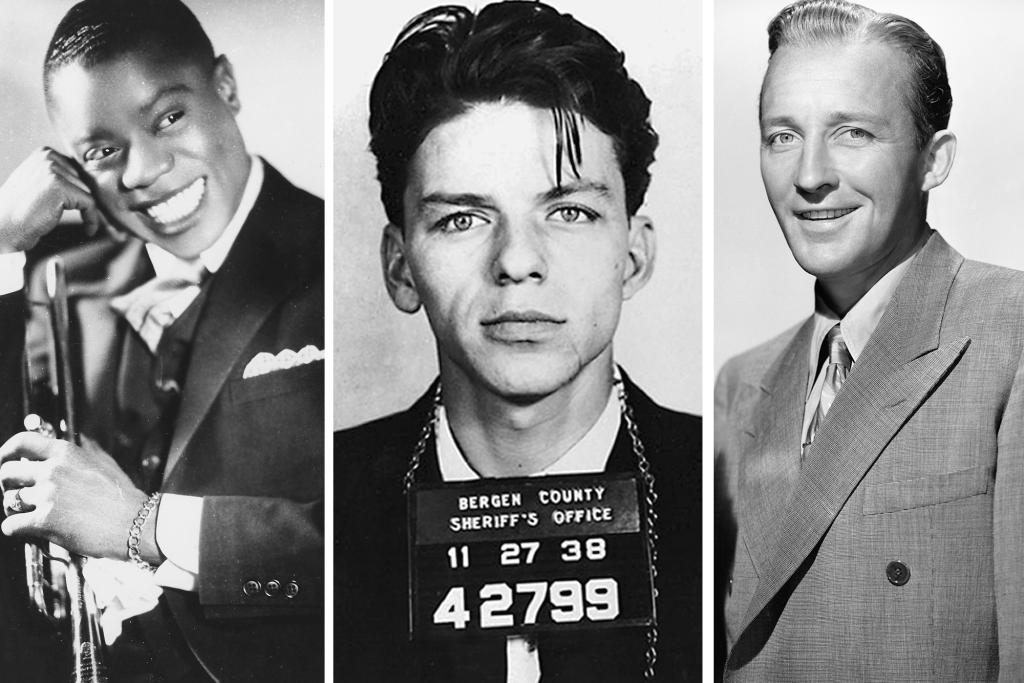

Author TJ English’s latest book, “Dangerous Rhythms: Jazz and the Underworld,” due out August 2, explains why jazz greats like Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, and Frank Sinatra thrived in mafia empires led by Al Capone, Meyer Lansky, John T. “Legs” Diamond and Charles “Lucky” Luciano.

“Jazz began at the end of a long, ongoing period of lynching after the Emancipation Proclamation,” Engels told The Post, speaking from his home in Manhattan, where he has lived for 32 years. “The music seems to me to be an attempt to create a new reality,” he added. “The music says, ‘We’re still alive.’ I see jazz as a response to terror and violence.”

Engels, who has written several books about the criminal underworld as well as episodes for TV’s “NYPD Blue” and “Homicide: Life on the Street,” said the unlikely connection between black musicians and Italian mobsters made sense in the context of an oppressive social order from the turn of the century.

Jazz first started buzzing in New Orleans, where Sicilian immigrants and black Americans faced the same predicament: they were locked out of wealthy white Anglo-Saxon Protestant society and harassed by corrupt white police officers.

“Black people had less to fear from a mob boss than a white police officer,” said English, a self-proclaimed jazz fan. “They saw the mafia as their protection in the commercial market. That was very true for Louis Armstrong. He knew you had to have your gangster for protection. Louis said, “Buy the biggest mobster you can get.” ”

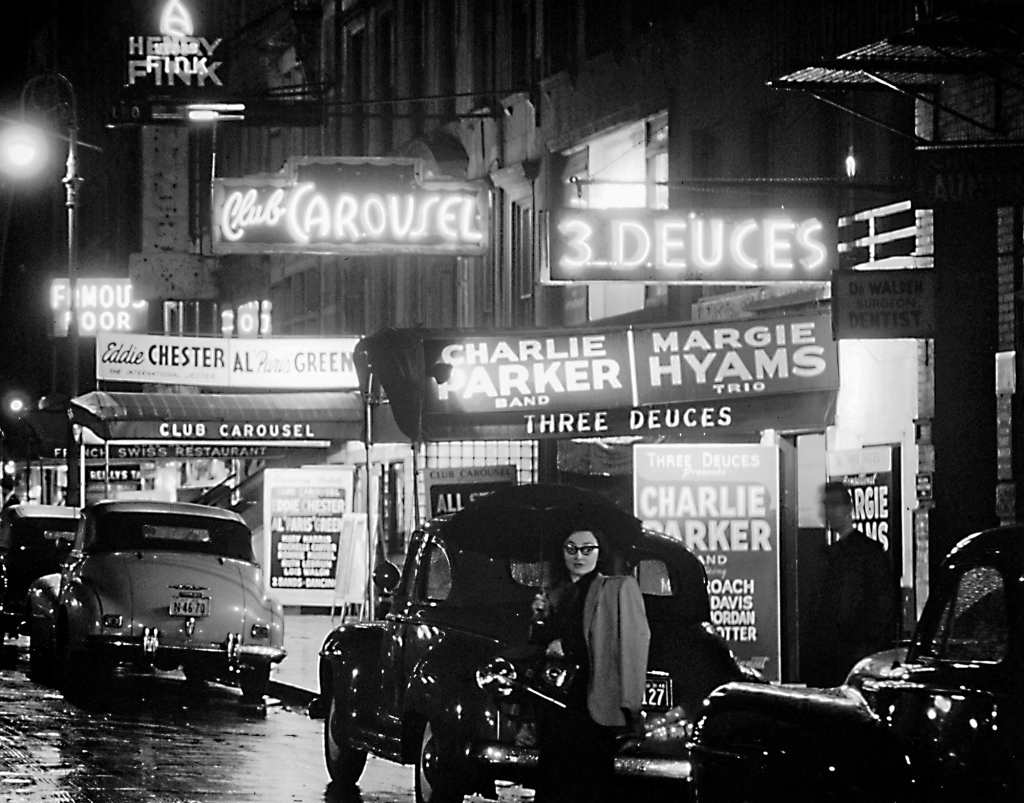

The New Orleans recipe—where black performers joined gangsters who oversaw one of the country’s first legal red light districts, Storyville, where brothels and bars thrived—spread to Kansas City, Chicago, New York, and then Las Vegas. .

In 1920, Prohibition ushered in a new era for nightlife as white society began to flow into speakeasies.

“They went where the booze was,” Engels said. Nightclubs became socially acceptable, jazz entered mainstream entertainment even though society otherwise remained segregated, and the underworld stew became the entertainment business model.

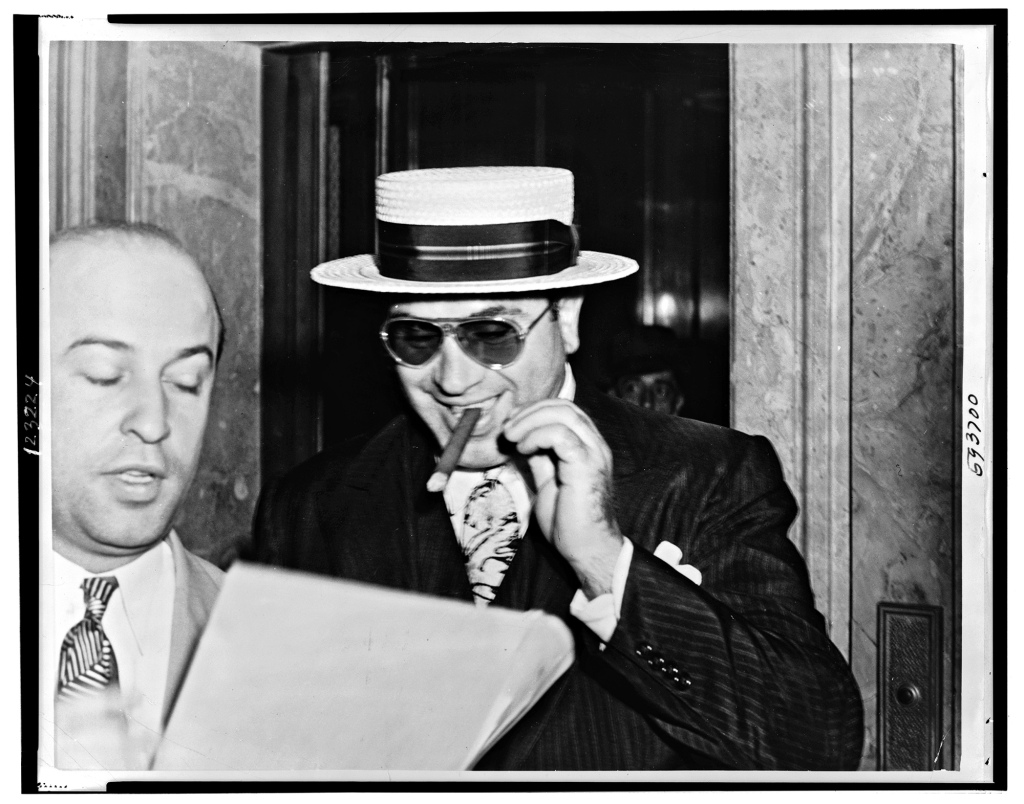

And many mob boss could really appreciate jazz.

“[Al] Capone was the greatest benefactor. He loved the music,” said English, adding that his accomplices once “kidnapped” New York City-born Fats Waller after performing in Chicago in 1926 to surprise Capone for his birthday. Waller was greatly relieved when he realized what was happening. “[Capone] was good for the musicians: he spread the money in the jazz world.”

In addition to firing on entertainment and booze, mobsters continued to stick to their part of the bargain to keep performers safe.

By the late 1920s, white performers had co-opted jazz, and artists like Bing Crosby mainstreamed the sound and perfected vocal pop jazz. By 1932, Crosby was one of America’s biggest singing stars, and when a mobster tried to take advantage by extorting Crosby for protection money — that is, protection from the mobster who beat him up — the mob stepped in.

“Crosby was raking in the dough at that point and his management, MCA, had connections to the mob,” Engels said. “MCA sent a mobster named Jack McGurn to handle it. McGurn grabs the man and kicks the s–t out of him and Bing has never been blackmailed again.”

Bing and Jack—aka “Machine Gun Jack,” who allegedly took part in the 1929 Valentine’s Day Massacre, when seven Irish mobsters were shot by Capone’s rival Italian crew—became golf buddies afterward.

But “the greatest singer in the United States who played golf with a mobster didn’t look so good,” Engels said. “So Bing ended the friendship. Jack was actually murdered eight months later, so maybe it was wise to end it.”

Even as jazz became an all-American music and the genre spread into different styles, from Crosby’s crooning to wild swing and then bebop, its links to the criminal underworld and gangsters, Italian, Irish or Jewish, were closely linked.

“The most popular club in New York City in the 1940s was Birdland, owned by Mo’ Levy, a mobster who sold heroin from the club,” recalls English.

Mo’s brother Irving ran the club and was happy to have big stars like Marlon Brando and writers like Norman Mailer as regular customers. One night in 1959, Irving was stabbed and killed by a pimp while the band was playing. “It was sensational,” Engels said. A newspaper headline read, “Jazz serves as a backdrop to death.” ”

Then came the Rat Pack and Old Blue Eyes, who ruled the modern pop jazz scene, and their headquarters, mafia-created Las Vegas, became the epitome of glamorous American nightlife and “The Good Life.”

“Sinatra’s relationship with the mafia was very specific, very real,” said English. “The mobsters ran the casinos and the clubs and booked the music they liked.”

Which in the 1960s didn’t sit well with young people clamoring for the British Invasion or the anti-establishment hard rock of hippie culture.

“Young people thought Vegas was hokey. The music was music their parents loved,” Engels said. Jazz, once the music of rebellion, was beginning to sound old-fashioned compared to the pop, rock and soul of youth culture, and the mob’s grip on the entertainment industry was beginning to crack. In the eighties the old gangster world had collapsed and jazz lost its financial support.

By this time, however, jazz was being recognized for its artistic merits, and cultural institutions such as Jazz at Lincoln Center stepped in.

“[At the beginning] there was no patronage from the institutions of culture and wealth,” said Engels. “Jazz wouldn’t happen at that level. It had to earn its place at the table.”

That would never have happened without the mafia and the artists who kept quiet about what they saw for decades.

“They kept their mouths shut,” Engels said of the musicians. “They played, got paid and didn’t talk outside of school.”

Engels said that’s ultimately because the gangsters and the jazz greats were united in the same goals, and that’s all that mattered to them.

“It was really the same pursuit of the American dream,” Engels said. “Just out of the gutter.”