Researchers at Linköping University and Sweden’s Royal Institute of Technology have created the world’s first wood-based transistor, paving the door for eco-friendly wood-based electronics and control over “electronic plants.”

“We’ve come up with an unprecedented principle,” says senior associate professor Isak Engquist, corresponding author on the groundbreaking study. The wood transistor is slow and cumbersome, but it works and has great future potential. The wood transistor was designed without a purpose. We could. We hope this basic study may inspire future applications.

Researchers at Linköping University and Sweden’s Royal Institute of Technology have created the world’s first wood-based transistor, paving the door for eco-friendly wood-based electronics and control over “electronic plants.”

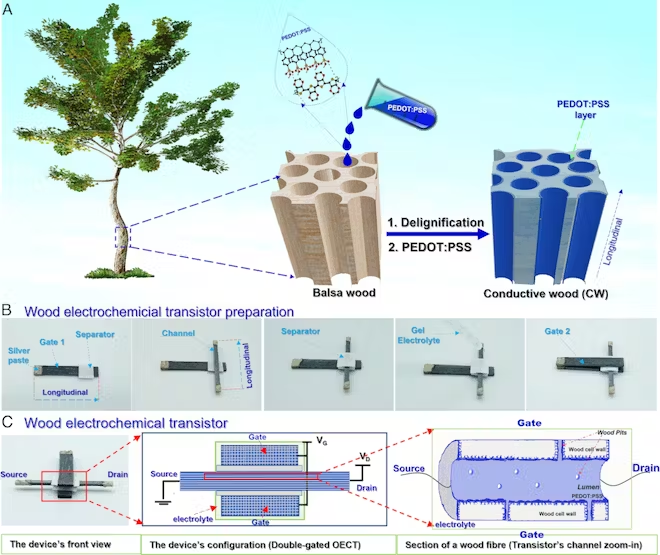

Slow wooden transistor is a first step made of balsa wood treated with conductive plastic polymer.

“We’ve come up with an unprecedented principle,” says senior associate professor Isak Engquist, corresponding author on the groundbreaking study. The wood transistor is slow and cumbersome, but it works and has great future potential. The wood transistor was designed without a purpose. We could. We hope this basic study may inspire future applications.

John Bardeen, Walter Brattain, and William Shockley at AT&T Bell Labs in 1947 and 1948 produced the transistor, patented in 1925 by physicist Julius Edgar Lilienfeld.

The transistor, designed to replace the thermionic triode vacuum tube, was smaller, lighter, and more dependable. In the decades afterwards, it has been downsized to the point where a single integrated circuit can contain billions of them in a tiny footprint.

The Swedish researchers’ prototype, manufactured from balsa wood with lignin removed and hollow channels filled with conductive plastic polymer, functions similarly to the Bell Labs prototypes. The device transmits electricity and may operate continually, unlike earlier wooden electronics.

Though groundbreaking, the prototype has some drawbacks. The first is size: while smaller than Shockley and colleagues’ point-contact transistor prototype, it’s huge compared to modern silicon transistors. The researchers say activating and deactivating the device takes five seconds each.

The researchers believe the technology can regulate “electronic plants” and be used in higher-current situations where competing organic transistors fail.

The Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation’s Wallenberg Wood Science Center supported the team’s open-access PNAS publication.