As Josephine Baker moved through international checkpoints in Spain and Morocco, the dancer and singer teased the officers who asked to see her papers, saying they just wanted her “signature.”

Her official story was that she was on a “tour of Spain.” She was actually working as a spy for the Resistance, with state secrets neatly hidden in her bra.

Baker took the gamble that no one would dare to search her. She smiled her famous smile — she was the most photographed woman in the world at the time — as the documents “stayed securely in place, secured with a safety pin.”

Baker’s role as one of the true heroes of World War II, fighting the Nazis at great risk to himself, is detailed in Damien Lewis’ new book “Agent Josephine: American Beauty, French Hero, British Spy” (PublicAffairs). In 1961, she was awarded a Legion D’Honneur, France’s highest military service award, for her mission in Spain and Morocco, and was commended for obtaining “precious information.”

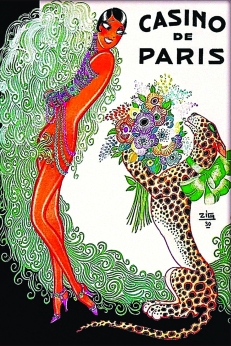

Josephine Baker, born in St. Louis in 1906, moved to France at the age of 19. She emigrated in hopes of leaving behind the racism that stood in the way of her American aspirations. She soon became famous for her singing and dancing, including her beloved act where she wore only a rubber banana skirt. She became friends with French celebrities such as the writer Colette. She bought a castle, wore dresses from the most exclusive designers and often walked the streets with her cheetah, Chiquita, who wore a diamond collar.

And for a while she was treated equally.

Once, when a visiting American who saw her dancing at the Folies Bergere theater remarked, “At home belongs a woman in the kitchen,” the room fell silent in horror.

“You are in France,” the manager replied curtly, “and here we treat all races the same.”

But dark forces arose in Europe.

In 1925, when Hitler’s “brown shirt” stormtroopers were still considered fringe groups, Baker performed in Berlin to thunderous applause. When she returned two years later—after Hitler became known for publishing his book “Mein Kampf,” which labeled black people “half-monkeys”—the reaction was quite different. German and Austrian headlines denounced her as a “black devil” and a “jezebel.”

“How dare they put our beautiful blonde Lea Seidl on stage with a negress?” asked one newspaper, while another claimed that “this colored girl’s convulsions” would undermine Dresden’s sense of dignity. The crowd was so large that Baker feared for her life.

Ten years later, Baker’s face graced the cover of a 1937 brochure denouncing decadent artists, published by Joseph Goebbels, the Nazi Party’s foremost propagandist. That same year, Josephine married Jewish industrialist Jean Lion. Her passion to fight the Nazis – and to defend her adopted country and husband, as well as herself – grew into a fever pitch. In 1938, she declared that Nazis were criminals and that “criminals should be punished.” She claimed she would kill them with her own hands if necessary.

![Not shy about proclaiming the evil of the rising Nazi power in Germany, Baker declared in 1938 that she would kill [Nazis] with her own hands if necessary.](https://vidakforcongress.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/1657999303_484_Josephine-Baker-was-a-tough-resistance-spy.jpg)

That same year, she was approached by the Deuxième Bureau as an Honorable Correspondent, a voluntary position that involved gathering intelligence for the bureau. It was completely unpaid, as is typical for such a role. Throughout the war, Josephine refused to take money for her work and sometimes resorted to selling jewelry and other possessions to fund her excursions.

Shortly after she started working as a spy, Baker learned through friends at the Japanese embassy that Japan had made a secret anti-communist pact with Hitler. It was the first of many pieces of information she would pass on to the agency. Shortly afterwards, she informed the agency that she had learned – through friends at the Portuguese embassy – that Germany intended to occupy neutral Portugal to use their ports. She quickly became one of France’s most valuable possessions. Espionage allowed Baker, as Lewis puts it, “to strike back, without necessarily ever drawing blood.”

When war broke out in France in 1940, Josephine’s glamorous manor – the Château des Milandes in the Dordogne – became a base for local members of the resistance, as well as for refugees, including a Belgian Jewish couple who hosted Baker there. A radio transmitter was installed on the tower for contact with Britain and the cellar was filled with weapons for the Resistance. When German soldiers came to investigate? after receiving a charge, Baker assured them that she was just a dancer.

But, she emphatically told them, “I wouldn’t have the heart to go on stage when there’s so much suffering.” In fact, Baker was on stage throughout the war — she just wouldn’t perform for Nazis.

As a star performer, Baker had a cover that allowed her to easily travel to other countries—from Portugal to Spain to Morocco—something most people couldn’t get visas for during the occupation.

“I come to dance, to sing,” she told journalists abroad who asked her why she left France. She had actually come to deliver letters, photos, and documents that might be useful to the Allies, and to meet people sympathetic to the cause of the Resistance. She carried sheet music with information written in invisible ink about the positions of the enemy defenses in southwestern France. She filled notes on other important details in her lingerie. Fellow agents traveled with her, posing as her “tour manager.”

Throughout the war she worked with “Berber leaders, Rif leaders” [from the Northeastern region of Morocco], Arab dignitaries, American troops both black and white, (former) Vichyites, plus the Free French troops.” Even when her friends were murdered by Nazis or sent to concentration camps, Baker kept her calm. While performing for American troops in northwestern Algeria, she survived enemy fire by diving near the buffet tent. A Texan soldier crawled over to her on all fours with a bowl of ice cream in front of her, which she happily ate.

Then she quipped, “Me, belly down, among soldiers from Texas, Missouri and Ohio in my 1900 Parisian dress, must have been an irresistibly funny sight. Mainly because I kept eating.”

After the war, Josephine returned to Germany in 1945. This time she was honored at the Allied victory ceremony at Hohenzollern Castle, the historic home of the German royal family. She took pride of place in a country that had humiliated and ridiculed her just a few years earlier. She then performed for the survivors of the Buchenwald extermination camp who were too weak to leave the prison. Though the camp was riddled with typhoid fever and still riddled with bodies, and Baker was in ill health, she still found the strength to sing a song called “In My Village” about the simple joys of home.

Even after France was liberated from the Nazis in 1944 and the war ended the following year, Baker never stopped fighting for equality for all people.

“She would never forget the lesson of the war years: freedom must be fought every day,” Lewis writes.

She died in 1975 at the age of 68. Dancing in a revue at the Bobino Theater in Paris until the day before her death in honor of her 50 years in show business, she said that “the war years” had been the pinnacle of her life.

“I gave my heart to Paris, as Paris gave me hers,” she said on stage during the opening night of the Revue.

In 2021, she was given her greatest honor: admission to the French Pantheon, which recognizes only the greatest figures of French history, such as Voltaire, Victor Hugo and Marie Curie.

She is one of only five women to earn a spot there.